However, the potential application of these methods to the valuation of options on real assets was soon identified, and given the moniker “real options.” Although hundreds of scholarly papers have been written on this topic, the complex mathematics required for option pricing techniques have unfortunately limited the appeal of these topics for many practitioners. Option pricing methods were first developed to value financial options. In this article, we discuss how this work can be further enhanced by applying an intuitive approach based on familiar concepts from the field of decision analysis. In recent work, Copeland and Antikarov, Copeland and Tufano, and others have sought to increase the application of more advanced valuation approaches by introducing computational methods that are more accessible to practitioners. Thus, we could have different revenues and cash flows than the ones shown in Figure 1, and the resulting present value would change as well.Īn approach that treats future decision-making opportunities as options can account for this value, but because these more advanced methods are less familiar to many managers, their widespread use has been slow to arrive in practice. If the firm indeed has the flexibility, we might instead expect management to revise the production level accordingly. For example, if the product unit price in future periods increases or decreases significantly, relative to the expected prices used in Figure 1, it seems untenable to assume that the firm’s management would fail to respond to such a change. Unfortunately, this approach ignores the significant incremental value that can be derived from management’s response to conditions in the future. In such cases, the practitioner must exercise judgment in choosing an appropriate discount rate for the project. While this assumption may be valid for projects that mimic the risks associated with the firm as a whole, it may not be appropriate for unusual or innovative investment projects. In practice, this discount rate is often the weighted average cost of capital for the firm (WACC), based on the assumption that both the firm and the project have the same risk level. The cash flows should then be discounted at a rate that is commensurate with the riskiness of the project.

#REAL OPTIONS VALUATION EXAMPLE PRO#

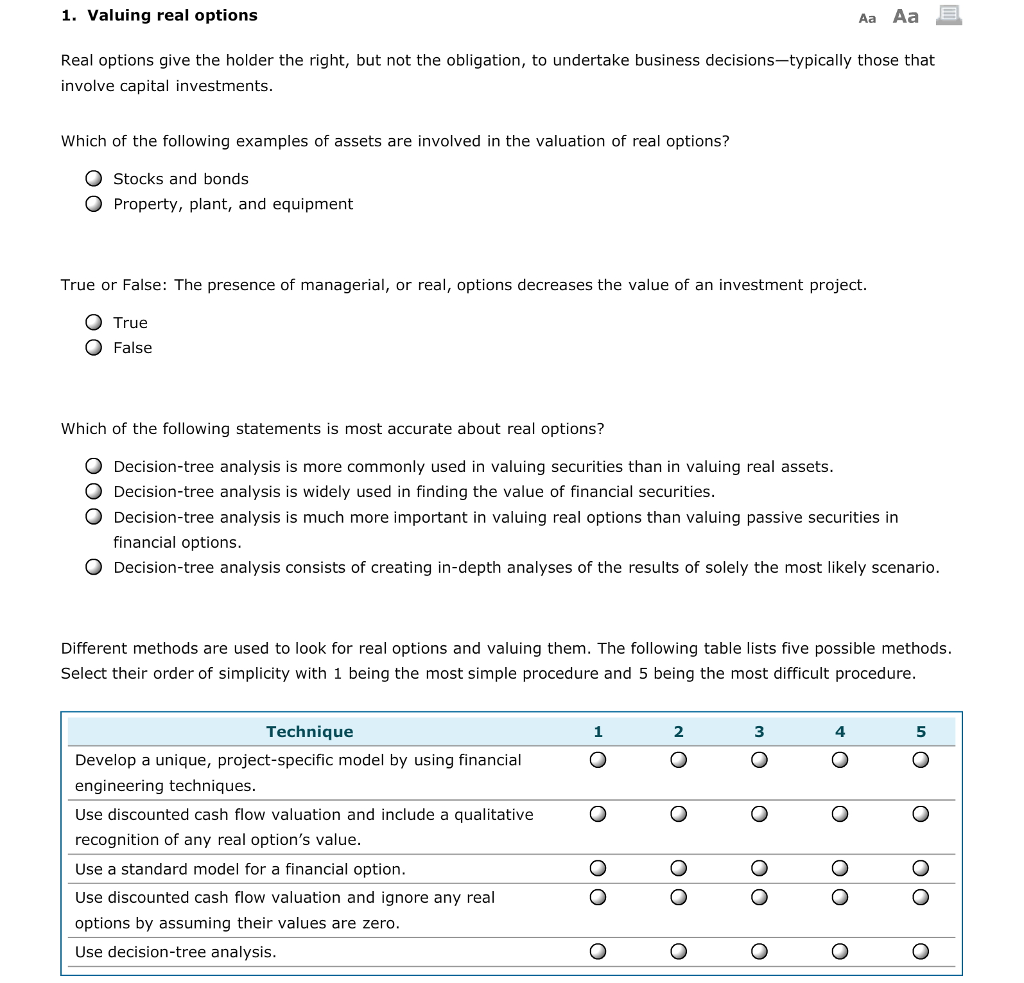

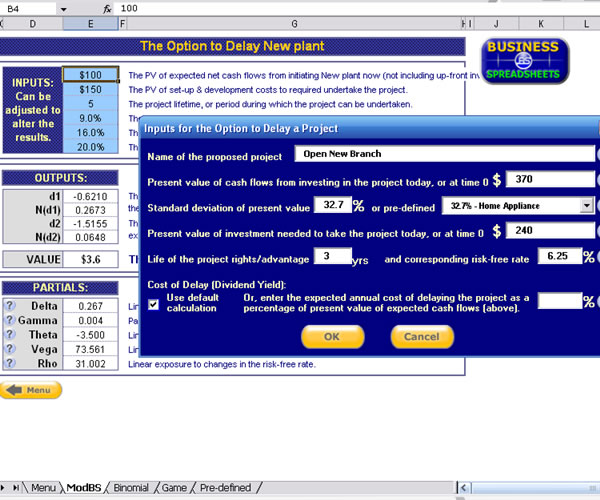

In the pro forma, the production and price forecast in each period translate to revenue, which can then be netted of production costs to arrive at the expected cash flow in each period. This example might be representative of a typical industrial manufacturing application with a three-year production planning cycle under a forecasted market price environment. Figure 1: Pro Forma Cash Flow Sheet for Simple Three-Period Project As an example, consider a simple three-period project for which a pro forma cash flow sheet is shown in Figure 1. With the DCF approach, the net present value of a project is calculated by discounting future expected cash flows at a given discount rate. Asset Valuationįor quite some time, discounted cash flow methods (DCF) have been the primary approach used by practitioners for the valuation of projects and for decision making regarding investments in real assets. By merging decision analysis with the well-known principles used in valuing options on financially traded assets, we can quantify the potential value associated with these types of options on real assets. This is especially important for projects with built-in flexibility, such as those with options to expand operations in response to positive market conditions, to abandon an asset that is underperforming, to defer investment for a period of time, to suspend operations temporarily, to switch inputs or outputs, to reduce operational scale, or to resume operations after a temporary shutdown.

One of the primary responsibilities of a management team is to make decisions during the execution of projects so that gains are maximized and losses are minimized.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)